Scary Stories and Staying Power—TAMUC Professor Shines a Spooky Light on a Children’s Horror Classic

Part 1 of the Spooky Story Series

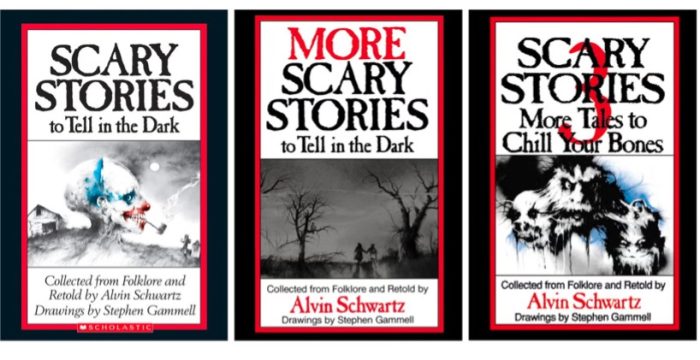

For many of us, a childhood rite of passage was to get our hands on a book from Alvin Schwartz's “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” series. The spine-chilling tales and Stephen Gammell's horrifying illustrations kept many of us awake at night. Because of this, “Scary Stories” have been among the most challenged children's books, resulting in many bans from schools and libraries. Yet, the series has been loved and cherished for over 40 years. The question we ask is, “Why?” Why have children across the decades treasured a book that adults have feared will scar them for life?

Dr. Rebecca Rowe, a children's literature scholar and professor in the Department of Literature and Languages at A&M-Commerce, offered some insight. Rowe has researched book banning and society's attempts to protect children from certain book topics. Naturally, her research has included looking into Schwartz's “Scary Stories” series.

A Look Back at “Scary Stories”

For context, the “Scary Stories” series was originally published in the early 1980s, and according to the Hollywood Reporter, has sold over seven million copies. In 2018, a documentary was made about the series, discussing its cultural significance, and in 2019, the books were adapted into a horror film (which seemed to target “90's kids” who cherished the series and were drawn in by nostalgia).

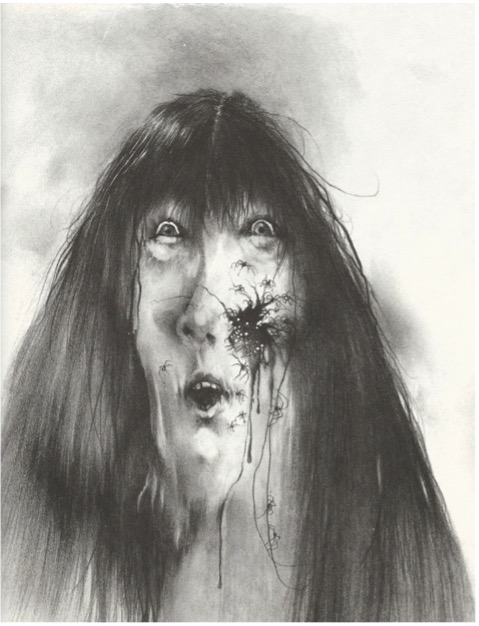

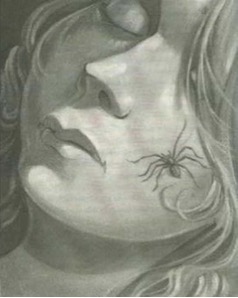

Looking back at the original texts, it's hard to deny that they are not just spooky—they are genuinely horrific. The collection features stories like “Harold” (about a scarecrow that comes to life and skins a man as revenge for throwing things at him), “The Red Spot” (about a pimple on a young girl's face that grows larger and larger and turns out to be a nest for spider eggs), or “Just Delicious” (about a woman who feeds her husband their dead neighbor's liver).

Gammell's illustrations are just as frightening as the stories, if not more. Thirty years after their original publication, “Scary Stories” changed publishers from Scholastic to Harper Collins and was given a new illustrator, Brett Helquist, to ease parental concerns. But many who read “Scary Stories” as children have expressed sadness and frustration over the loss of the original creep factor, saying the books aren't the same without the grim and unnerving illustrations.

Rowe admitted that she never actually read the books as a child. “I'm a huge scaredy-cat,” she said, chuckling. In fact, she never picked up the books until she was in graduate school, studying children's literature and researching banned books. Despite this, “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” was still a looming figure in Rowe's childhood.

“I think I was in like third or fourth grade,” she recalled, “and everyone I knew was reading it. Like, it was to the point where they were reciting it. It was a huge part of my childhood, even though I never read it. I heard all the stories because kids were telling them all the time.”

As an adult, the memory of hearing classmates recount “Scary Stories” has remained with her, as the stories have remained with so many of us. Rowe explained that the series has “staying power” for several reasons.

The Staying Power of “Scary Stories”

1. The stories are timeless.

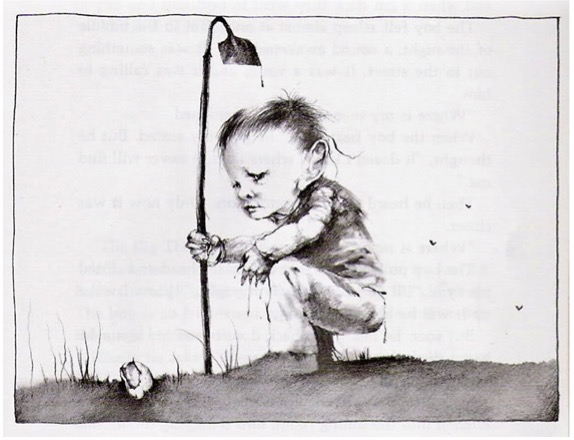

Although Schwartz is often considered the author of “Scary Stories,” he was more of an editor and compiler, collecting folklore and legends and assembling them together. According to Rowe, Schwartz chose stories from folklore that practically don't age because they all speak to fundamental human fears.

“A lot of the stories fall under what's called ‘uncanny valley,' which is this concept of things that are almost human but aren't quite, and it freaks our brains out,” she explained. “It's something that's almost hardwired in our brains as humans, across cultures and throughout time: we tell these stories because we're trying to deal with what it means when something's not quite human (or at least human in the way we define it).”

Basically, fear ages well because, in a way, it doesn't age at all. It doesn't matter if you are 12 or 112, lived in the 1980's or 2020's, the idea of a spider laying eggs in your face is terrifying!

2. They're a communal experience.

Like many legends and folklore stories, “Scary Stories” are meant to be experienced with other humans. In the text, there are cues for the reader and instructions on interacting with listeners.

For example, in the story “The Big Toe,” a young boy finds a human big toe in the ground, pulls it up, and brings it home to his mother and father to eat for dinner (because who doesn't look at a decapitated big toe and think “Yum”?). That night, the boy hears an eerie voice calling, “Where is my tooooeeee?” The boy tries to hide, knowing the toe's owner is coming after him. In the text, Schwartz writes in parenthesis to the reader: “At this point, pause. Then jump at the person next to you and shout: YOU'VE GOT IT!” In other parts of the book, Schwartz tells the storyteller to turn off the lights, whisper and scream to startle the listeners. Rowe explained, “These are stories to tell. They are intended to draw people together around the campfire. Several generations of kids have been telling each other these stories and trying to scare each other, so I think that's another reason these have had staying power—they're not meant to be experienced alone.”

3. They treat children as capable readers.

“Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” is truly scary. Terrifying. Nightmare-inducing. So, it can be surprising that children love them. Rowe explained that contrary to our societal belief that children are fragile and easily frightened, kids truly like being spooked almost as much as adults.

“We like to pretend children need to be protected, but kids really enjoy the feeling of being scared, especially when they have control over it. They can read it, experience it, and if it gets to be too scary, they can choose to put the book down.”

Children's horror is an entire genre within itself, and one of the common traits of the genre is that it treats children like any other reader and doesn't try to “level down” the fear factor.

“Schwartz did this so well,” Rowe said. “He didn't bring ‘Scary Stories' down to a level for children. He was just like, ‘Here's a scary story; you deal with it, goodbye.' And I say those are the best because they acknowledge that children have intelligence and capabilities and can deal with these things.”

4. They are visually driven.

It's already been mentioned that Gammell's original illustrations are iconically horrific. Rowe explained that, as a child, she was willing to hear the stories but adamantly refused to look at the book. Pictures and illustrations affect us because we are (and always have been) a very visual culture.

Rowe laughed as she said, “I mean, in current days, we're communicating with emojis. Like, we've essentially gone back to hieroglyphs!”

Because of our visual culture, images mean a lot, especially when they have a distinct or easily recognizable style like Gammell's. Rowe also suggested that readers were so upset about the illustration change because it changed the point of the entire book.

“These illustrations were designed to scare you, and then the new ones try to put the kid gloves on. It goes back to acknowledging children as capable readers. When you try to put child safety locks on it, it loses some of that power, and that feels wrong.”

“Scary Stories”: Delightfully Terrifying

Despite considering herself afraid and having never actually looked at the book as a child, Rowe could name her favorite story from Schwartz's collection. It's called “The Haunted House,” and Rowe summarized it well: “It's the one where the preacher goes to the haunted house and a ghost appears and says, ‘Take my finger bone and put it in the offering plate, and the guy who killed me will be revealed.' I love that one, and that story has one of the creepier pictures in the collection.”

When asked if she had seen the 2019 film adaption of the books, Rowe answered with an emphatic, “NO! But I have heard it's delightfully terrifying.”

That phrase, “delightfully terrifying,” is an excellent way to describe why “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” has been so important for so long. Because regardless of our age, we love to be spooked. We jump in fright and laugh in joy. We cringe at the horror and lean in to hear more. When compiling stories and creating the series, Schwartz knew that love of fear was in all of us, whether children or adults. He and Gammell tapped into that, creating something with “staying power.”

Alvin Schwartz passed away in 1992, but through “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark,” his voice has spoken to us for decades. And perhaps, whenever a child eerily asks their friend, “Where's my toooeeee?” and then pounces to scare them, his ghost gets a little chuckle.

____

Did you know you can study fun and interesting things like this in college? Dr. Rowe teaches numerous children's literature classes to both undergraduates and graduate students. A&M-Commerce also offers a graduate certificate in children's and adolescent literature for master's and Ph.D. students.

Don't miss out on the rest of our Spooky Stories in October!

Top photo: The Covers of All Three “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” series, drawn by Stephen Gammell, Scholastic.

More Literature & Languages

View All Literature & Languages

A&M-Commerce Faculty Named Prestigious Fulbright U.S. Scholar

TAMUC Assistant Professor Eralda Lameborshi, Ph.D., received the prestigious Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award.

A&M-Commerce Professor Receives Prestigious Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award

Dr. Maia Lamarque, a professor in the Department of Literature and Languages at Texas A&M University-Commerce, has received a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award for the 2024-202...

TAMUC Co-Hosts Privacy Week to Explore Digital Privacy

A&M-Commerce played a significant role in organizing and hosting an international event to promote discussions about digital privacy i...